Rb-doped LTOs with various doping levels (Li

4-xRb

xTi

5O

12;

x = 0.010, 0.015, 0.020) were prepared via ball milling and subsequent solid-state reaction at 850°C. For comparison, neat Li

4Ti

5O

12 (

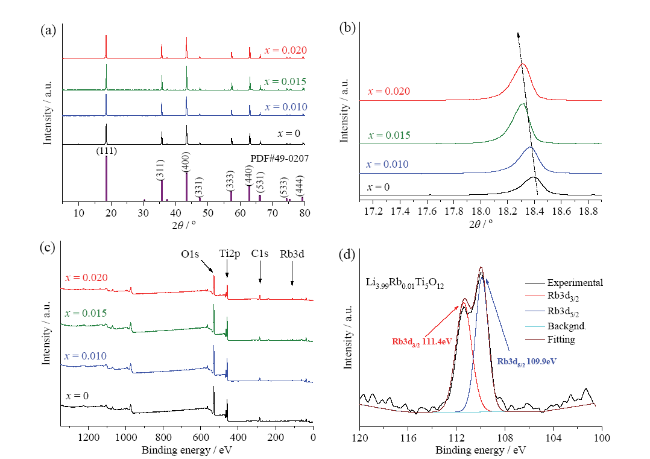

x = 0) was synthesized under the same conditions. XRD patterns of Li

4-xRb

xTi

5O

12 (

x = 0, 0.010, 0.015, 0.020) are displayed in

Fig. 1a. Diffraction peaks at 2

θ = 18.4°, 35.6°, 43.2°, 47.4°, 57.2°, 62.8°, 66.1°, 74.3°, 79.3° are attributed to (111), (311), (400), (331), (333), (440), (531), (533), (444) planes of Li

4Ti

5O

12 spinel (JCPDS#49-0207)

[5,42]. The magnification of (111) crystal panel peak at 18.4° shows the shift of the peak to the lower angle with the increase of doping level, indicating that Rb successfully incorporated into the LTO lattice, occupying Li 8a site, and increased its lattice parameter (

Fig. 1b). XPS survey spectra of Li

4-xRb

xTi

5O

12 (

x = 0, 0.010, 0.015, 0.020) identify O 1s, Ti 2p, Li 1s peaks of main elements (

Fig. 1c). In addition to these elements, Rb 3d peak is detected for all Rb-doped samples Li

4-xRb

xTi

5O

12 (

x = 0.010, 0.015, 0.020), indicating the successful doping of Rb

+ in the structure

[23].

Fig. 1d shows the two peaks at 109.9 eV and 111.4 eV corresponding to Rb 3d

5/2 and Rb 3d

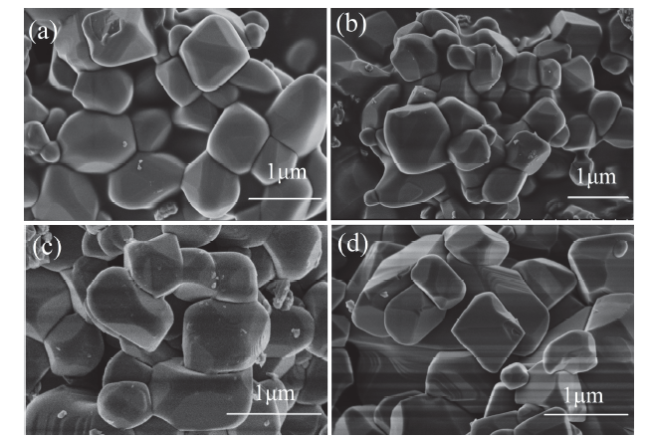

3/2. SEM shows that Li

4-xRb

xTi

5O

12 (

x = 0, 0.010, 0.015, 0.020) particles all have similar morphologies with almost cubic shape and the particle size is in the range of 0.2-1.5 μm (

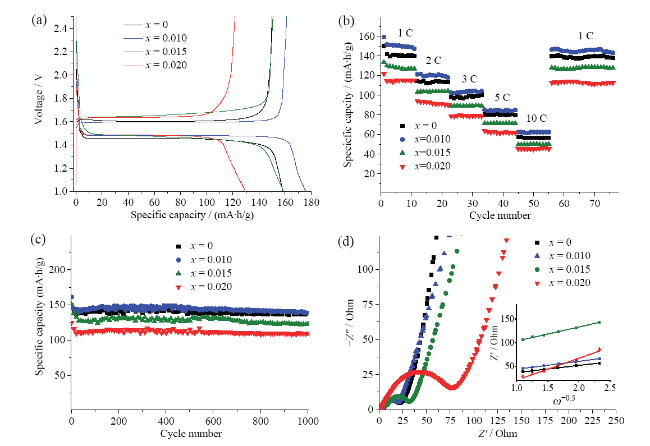

Fig. 2). The electronic conductivity was measured using a powder conductivity apparatus at 25°C. The obtained values are 3×10

-8 S/cm, 11.2×10

-8 S/cm, 12.5×10

-8 S/cm, 17.5×10

-8 S/cm for Li

4Ti

5O

12, Li

3.99Rb

0.01Ti

5O

12, Li

3.985Rb

0.015Ti

5O

12, and Li

3.98Rb

0.02Ti

5O

12, respectively. Obviously, Rb doping enhances the electronic conductivity of LTO, which can be attributed to the increase of lattice parameter due to the replacement of Li

+ atom by Rb

+ with larger ionic radius

[12,37].